"No garden can really be too small to hold a peony. Had I but four square feet of ground at my disposal, I would plant a peony in the centre and proceed to worship."

And thus we are introduced to another Lost Lady of Garden Writing, Alice Harding (Mrs. Edward Harding).

Alice, as I'm going to call her throughout this article, was rather elusive for me to find online until I searched for "Alice Harding Plant." This eventually took me to an extensive article about Alice on the Historic Iris Preservation Society Website. (Well done, and well worth reading!)

They noted that at the time of her death in 1938, "two irises, two herbaceous peonies, one tree peony, two lilacs, and a rose had been named in her honor by some of the most respected hybridizers of the day."

Her Biography

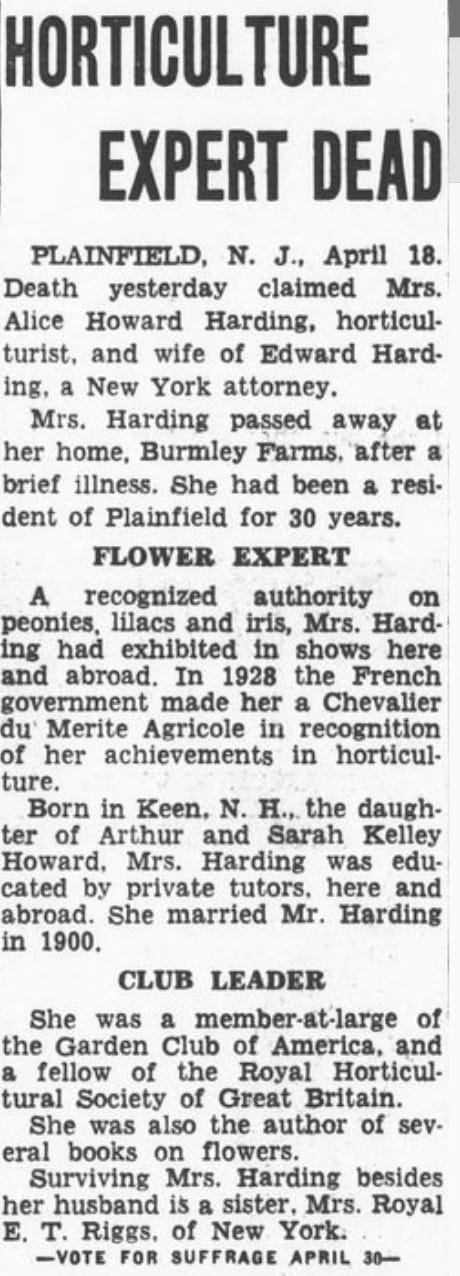

After several searches, I am fairly certain that “our” Alice was born Alice Howard in New Hampshire on September 26, 1871, was educated at home by private tutors, and later studied abroad. She married Edward Harding, an attorney, in either 1900 (per her obituary) or 1909 per another record I found—a passport application.

I also found some confusing records about a possible daughter, born in 1895, from the Find-A-Grave website, but if I found the right census records, there were no children listed in 1910, 1920, or 1930, and she didn’t get married until 1900 or 1909, so I am inclined to believe that either I made a wrong turn on Ancestry or someone else did, or perhaps Edward Harding had a daughter from a previous marriage. Regardless, there was no mention of children in either Alice’s or her husband’s obituaries.

But I don’t have the time nor inclination to sort that all out. “Alice Harding” and “Edward Harding” are surprisingly common names on Ancestry.com and Newspapers.com, especially when they pull in records from Great Britain. So in my mind, Alice had no children and devoted herself to gardening and hybridizing, with focus on peonies, irises, and lilacs.

She and Edward lived in Plainfield, NJ, on their estate called Burmley Farm where Alice grew many of the peonies and lilacs she wrote about, plus plenty of irises. My searches for information about this farm did not come up with anything except some lovely pictures in general around Plainfield, NJ.

Per her obituary, Alice died in 1938 after a brief illness.

Her Books and Other Writings

I found Alice on my own bookshelf via her second book on peonies, Peonies in the Little Garden (1923), the third book in the Little Garden series edited by Mrs. Francis King.

Her first book was The Book of the Peony (1917), and it was from this book that it appears Mrs. Francis King discovered Alice and subsequently asked her to write Peonies in the Little Garden. In 1993, Timber Press reprinted both books together in a book called The Peony. Good used copies are still available, as they say.

Alice also wrote a third book, Lilacs in My Garden (1933). It is notable for also being translated into French.

I cannot find where Alice wrote articles for magazines or newspapers, or that she traveled around to do much speaking. Those writers who also spoke to groups are often mentioned in newspaper clippings or society columns. My searches for articles, columns, and public appearances came up with almost nothing.

Perhaps Alice was just too busy traveling and so confined her writing to her books?

Her Travels

Her work with peonies and other plants took Alice overseas, probably on several occasions. She wrote about one such trip in her book, Peonies in the Little Garden, which occurred in the early spring of 1919, after World War I.

"In March of 1919 I had a wonderful opportunity to see the battle-fronts of Europe from Nancy to Ostend. A sadder, more appalling vision of destruction never was. Town after town was leveled to heaps of brick and dust; tree after tree was deliberately sawed off and left to rot. The grapevines were pulled up, the fruit trees girdled, the land itself so shattered and upheaved that the gardener's first query was whether it could again bear crops before the lapse of many years.

We had left Amiens one Sunday morning, and passing Villers-Bretoneaux—where Australian troops and some American engineers had made the stand that saved Amiens and the Western line—had gone through Hamelet, Hamel, Bayonvillers, Harbonnieres, and Crepy Wood to Vauvillers. As the only woman in the party, I had been unanimously appointed in charge of the commissariat. It was noon when we reached Vauvillers. I chose a broken wall about fifty feet from the road as a good place on which to spread our luncheon. The car was stopped, the luncheon things were unpacked, and we picked our way over the mangled ground to the fragment of wall. As I passed around the end I came upon two peony plants pushing through the earth. Tears brimmed. I could not control them. Here had been a home and a cherished garden. As I stood gazing at the little red spears just breaking through the ground, a voice, apparently from the sky, inquired whether Madame would like a chair. Looking along the wall I saw the head of an old peasant woman thrust through a tiny opening. She smiled and withdrew, appearing a moment later with a chair. It was her only chair. She then brought forth her only cup and saucer, her only pitcher filled with milk, and offered us her hospitality!

Joined now by her venerable husband, we listened to their story. The hiding of their few treasures, the burial of their bit of linen, their flight to Paris, the description of the outrageous condition of the one room left for them to return to, made us burn with indignation. It was in her little garden that the peonies grew. The fruit trees and shrubs were gone, the neat garden walks were blasted into space, the many precious flowers were utterly destroyed. When she found that Madame, too, loved les belles pivoines, (the beautiful peonies) she urged me to take one of the only two roots she had left!

We went away leaving the old couple laden with supplies, and I gathered from every man in our party a heavy toll of tobacco for a farewell gift of comfort. I hope she has again a little garden, with all the peonies that it will hold."

That is a wonderul story, not only showing the kindness of Alice, but also about the perseverance of people returning to their homes after World War I, not to mention the resilience of peonies, a universal flower recognized by both Alice and her hostess.

Today, you can probably still find some of the peonies, irises, and other plants named for Alice, by looking for the varieties named “Alice Harding” or “Mrs. Edward Harding.”

Her Gardening

As with other garden writers, I wonder how much of the work she did in her gardens and how much help she had in her gardens. I assume she had some help but also that she was quite involved with what was planted and how it was planted. In the first chapter of Peonies in the Little Garden she wrote:

“Yes – it is good to have a garden, and it is better still to work in it.”

I'll leave that as evidence that Alice did get her hands dirty in her garden.

In 1928, the French government made her a “Chevalier du Merite Agricole” in recogniton of her achievements in horticulture” per her obituary.

And so that is Alice Harding—Mrs. Edward Harding—a bit of a mystery today in some respects, but an honored and recognized horticulturist and author in her time. It is to her credit that her books were reprinted in the 1990s and that still today, you may stumble across a flower or two named in her honor.

As always, if you have additional information or insight about Alice Harding or any other lost lady of garden writing that I’ve featured here, I’d love to connect with you and find out more.

And if you know of any other lost ladies of garden writing that you think I might find interesting, leave a comment!